Custom fonts and CSS on Squarespace

If you’re using Squarespace, or using it for a client, part of the appeal is that you can control the template design without needing to know how to build websites. But what about when:

- you need to make a specific visual change to the template that isn’t possible through the dashboard?

- you need to use specific typefaces for a client’s visual identity, and they aren’t available on Squarespace?

- you want to differentiate your site from the many, many other sites using the same template out there?

In these situation, Squarespace is already working for you or your client—it almost certainly doesn’t make sense to change how or where the whole site is built. Instead, Squarespace provides the option to write or paste in custom CSS and JavaScript into the template, which you can use to make the small changes you need, while leaving everything else in tact.

The custom CSS feature in particular makes it possible to use consider and use a wider range of typefaces for your template.

Getting started

Squarespace already supports Google Fonts and Typekit, a great way to help differentiate your Squarespace site, or bring it more in line with your existing visual identity, is to use typefaces that aren’t already available to other Squarespace customers.

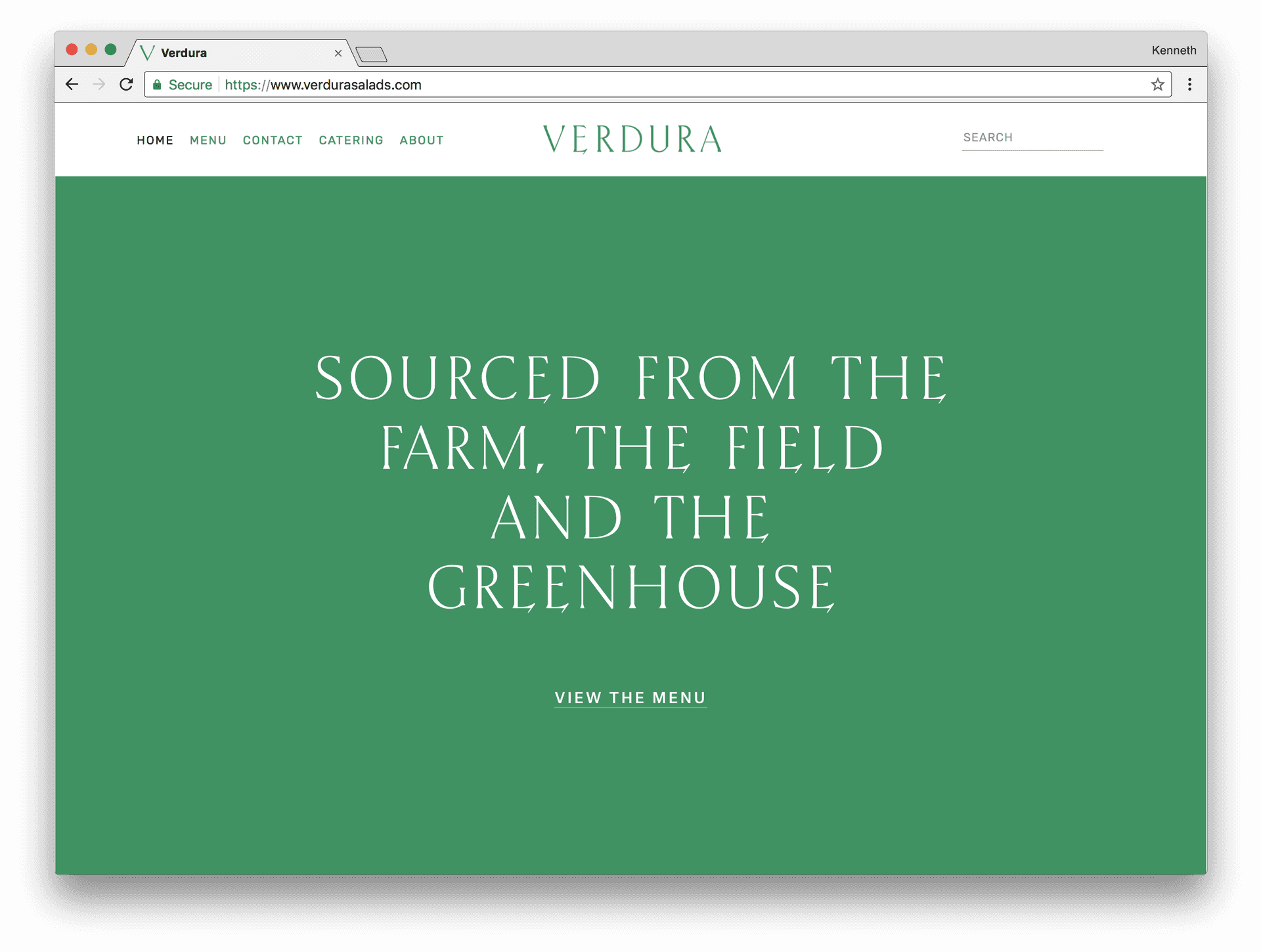

Perhaps you’ve purchased web fonts from an independent foundry, or maybe you’re event working with a custom typeface for your client—for example, the display typeface Glasfurd & Walker and I worked on for Verdura:

This is possible to do on Squarespace by with some custom CSS. CSS stands for Cascading Style Sheets, and describes the presentation of HTML documents, which includes Squarespace.

Many of the visual settings within Squarespace you might change—font size, letter spacing, etc.—will be translated into CSS that is served to your visitors’ web browsers.

This guide will focus on one specific part of CSS: @font-face declarations. These define how custom fonts are used within CSS. That means we’re going to write a very small amount of CSS, but the remainder will all be handled by Squarespace, just like you’re used to.

If you already have a CSS file or snippet that was distributed with your web font files, you’ll learn what it means and how to modify it for use on Squarespace.

1. Uploading fonts to Squarespace

Your visitors don’t have these fonts installed on their own devices, however, which is why we need the custom web fonts

First, login to the Squarespace site you’re working on.

In Squarespace 7.1, you can find this under: Pages → Utilities → Website Tools → Custom CSS.

In the older Squarespace 7.0, navigate from the main dashboard to: Design → Custom CSS.

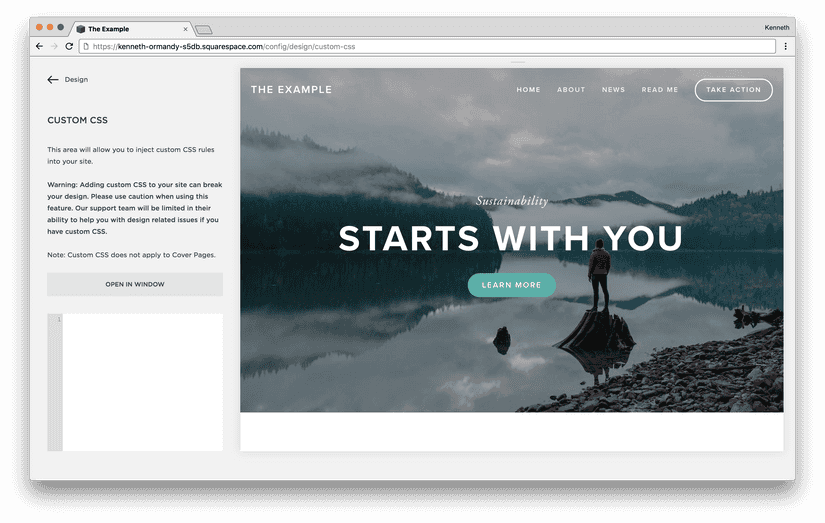

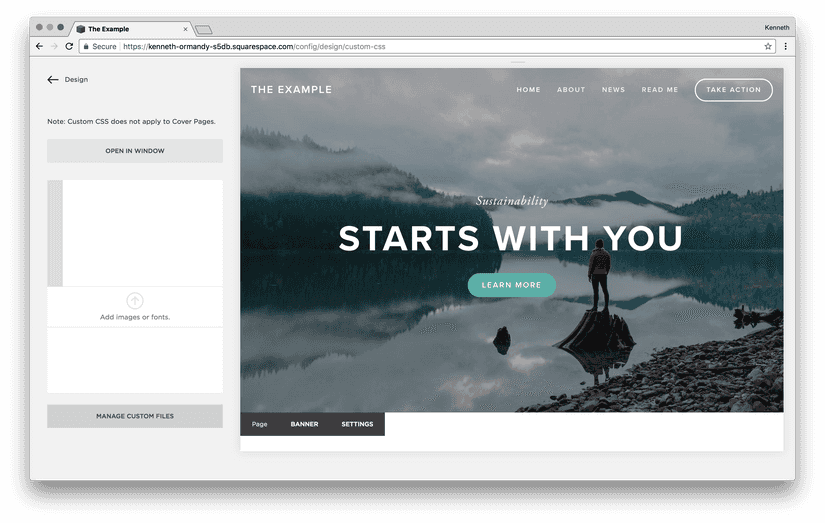

From here, you’ll be able to upload additional files you need for your site—in this case, web fonts.

Scroll to the bottom of the Custom CSS section, and press “Manage Custom Files.”

A section called “Add images or fonts” will open, where you can click or drag-and-drop the web font files you’ll want to use.

Formats you’ll want to use

You’ll probably have received a variety of formats from the type foundry you purchased these from.

- WOFF

- WOFF2

The WOFF and WOFF2 files are the formats you’ll most want. If you haven’t been given WOFF2 files, reach out to the foundry you got the typefaces from, and they’ll be able to generate them for you.

If you’re interested in more of the differences between WOFF and WOFF2, I wrote about it in 2014 in an article called Efficient Web Type, c. 1556 .

Upload these formats to the Squarespace site. If you have a lot of files and haven’t done this before, it might be easier to just start with one and go through the whole process, and then repeat it for the remainder of your files.

Formats you probably don’t need to worry about

Unless you’re in a specific industry or have specific traffic stats that show you need to support these browsers, it’s probably safe to stop worrying about these formats:

- EOT – For Internet Explorer 8 and earlier. Squarespace already shows a “Upgrade your browser” message to any visitors who might still be using these browsers.

- SVG – SVG fonts used to be provided to support much older versions iOS version 4.3 (Mar, 2011) and earlier.

- TTF – Sometimes these will be provided to support much older versions of Android 4.3 and earlier. The default Android browser has supported WOFF since Dec. 2013, and Chrome for Android has supported it for longer.

It’s particularly appropriate to omit these formats on Squarespace, because it’s likely your site hasn’t been formatted for or tested on these browsers.

2. Write or revise your @font-face declaration

Using the CSS editor is covered in more detail in Squarespace’s help article. I’m going to focus specifically on adding the CSS for the web fonts that were just uploaded.

It’s likely that, in addition to the web font files, you’ve been provided with a CSS file that looks something like this:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Example';

src: url('path-to-fonts/Example-Regular.woff2') format('woff2'), url('path-to-fonts/Example-Regular.woff')

format('woff');

}…although perhaps it lists all the formats we just went through.

In the this example, path-to-fonts/ is a placeholder, referring to the would be the name of the folder where the fonts are store, as if you were manually uploading all these files to a web server.

Squarespace, however, is handling all these file uploads and their location for us. A side effect is that the resulting URL is a little bit more complicated than a single folder name.

You can see where the fonts are stored by choosing one of the files you just opened. The URL will automatically be inserted into the CSS editor.

These URLs are quite long, so you might find this easier to work with in the full window version of the Squarespace CSS editor. Now, we’re going to write our complete @font-face declaration, so we can actually use the web font within our site.

@font-face declarations in the Squarespace editor. All code samples are provided below, please don’t squint to try and read the code in the gif. High-quality screencast videos come with the full version of this guide.First you’ll write:

@font-face {

}This is a new @font-face declaration, where you’ll define a single font family that you’ll be able to use throughout the rest of your CSS.

@font-face {

font-family: 'Example';

}Next, you’ll write the font-family property, and after the colon, you’ll set the name of the font-family in quotation marks.

You’ll use this font-family name elsewhere in your CSS, so technically it doesn’t actually need to relate to the real name of the font—although it’s probably easier to remember if it does. I’ve called mine 'Example'.

Now that there’s a single font-family name you’ll be able to use elsewhere in your CSS, we need to point to the actual web font file source, using the src property:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Example';

src: url() format('woff');

}If you were building your website from scratch, you could put a local url() within the parentheses, but since we’re hosting everything on Squarespace, this is going to be our Squarespace font file URL.

When you type the opening ( parentheses, Squarespace should give you an inline list of the files you might want to use, and you can use your cursor to navigate between them:

Alternatively, you can click between the () parentheses, and then click on your file from the list of uploaded files. This also works in the sidebar editor, as described in Squarespace’s documentation:

write your code to the point where you need the file url to reference. Then, leave the cursor where you want to place the URL in the code and then click the file. The CSS Editor will automatically paste the direct URL for that file so you can reference it in your code.

After the url, you need to specify the format of the file. For your .woff file, the format is 'woff'. For the .woff2 file, the format is 'woff2'.

Your example result look like this, but with the unique URL Squarespace provided:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Example';

src: url(https://static1.squarespace.com/static/abc/t/abc/abc/Example-Regular.woff)

format('woff');

}To add more than one source, each url() format() will be separated with a comma:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Example';

src: url(https://static1.squarespace.com/static/abc/t/abc/abc/Example-Regular.woff)

format('woff'), url(https://static1.squarespace.com/static/def/t/def/def/Example-Regular.woff2)

format('woff2');

}The order of the files is also important: WOFF2 files go before WOFF files, because the browser will use the first file it supports. If the mort recent WOFF2 format isn’t supported, the browser won’t bother loading it—a nice automatic performance benefit—and will automatically load the WOFF file instead.

The line breaks and spaces aren’t required for the CSS to be valid, but they will help make it easier for you to read.

3. Applying your font-family

The @font-face declaration you wrote in the previous section defines the source file, the default properties of the font (something I’ll cover in more detail later),

/* Below your @font-face declaration */

h1 {

font-family: 'Example', sans-serif;

}

You have now made it possible to apply our web font based on the font-family name we set. This can be done in a numbed different ways, including styling based on:

- A class name (like

.example) - An element name

- An ID based on the Squarespace template (like

#example)

…that’s already been set in the Squarespace template.

In nearly all scenarios, you want to avoid styling CSS based on an ID, and to avoid getting into the habit of that, we’ll avoid it here too.

In the full guide, I also cover:

- Troubleshooting, if your fonts still aren’t showing up as expected

- Loading and using multiple font styles

- Customising your CSS further, to target more specific pieces of your template (with a practical introduction to using your browser’s developer tools to find the class name of the exact element you want to target)

Using !important

Most CSS developers will advise that you avoid using a feature called !important, too: this allows us to override existing CSS set and make our own the most, well, important.

Writing CSS within the Squarespace interface is actually one of the rare situations where using !important can be encouraged, however. So, your earlier h1 CSS could change to:

/* Below your @font-face declaration */

h1 {

font-family: 'Example', sans-serif !important;

}Using !important is acceptable here for a couple of reasons:

- You aren’t responsible for maintain a template’s worth of CSS for many different users—you only need to worry about these few lines for you. You know for a fact you want to override Squarespace’s

font-familydecisions, no matter what. - If Squarespace modifies the specificity some of their template code in the future, or even changing a class name entirely, they will likely be using the same HTML markup underneath. For example, top level headings will still be

h1elements.

Learning more CSS, within constraints

If you’re still new to learning about CSS (or even if you’re not) I actually think environments like Squarespace can be a really useful environment to learn more about CSS specificity. One of my first really big CSS projects was creating a contemporary design for a ecommerce platform that was locked into a CMS that could modify the CSS but didn’t have control over the HTML—sound familiar? Within constraints, you can learn a lot about writing and refining your CSS, keeping what’s useful about Squarespace while still getting the visual outcome you’re after.